It all started with pumpkin pie. At our first outing, Emi-san tells me how much she loves the food of Thanksgiving. When someone goes to great length describing the food they miss, you know they do. “I just love it! I really do!” She mentions that the Costco pumpkin pie was too big for her to buy but had really wanted it. I make a mental note to buy a pie and invite her over, thinking, November is a long way off…….

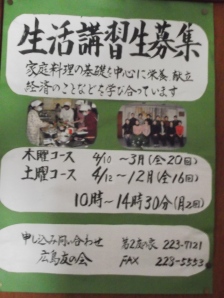

Halloween came and went. The November weather is beautiful in Hiroshima. The days feel like the Indian Summers of Idaho. Leaves turn without the cold temperatures. Gradually the green landscape turns a kaleidoscope of autumn. We continue to bike and explore on the weekends. Cooking school takes November off, but my days are full nonetheless. On our weekly trip to Costco, I check the bakery for pumpkin pie. November 28th still feels a long way off.

Emi-san has been so generous. She found me the cooking class. She taught me how to be a good Japanese neighbor, use the post office, and good local places to eat. To share a pumpkin pie is a must. My friends from the cooking school have also been lifesavers. They pick me up, take me to places and do things I could never without them. We have simple, laborious, authentic conversations that take up an amazing amount of time. Showing my gratitude by making a Thanksgiving luncheon seems the perfect symbol of my gratitude. As a last minute addition, I invite Lulu, she is a Micron spouse, and the same age as my cooking school friends. I know they will like each other.

As November closes there is talk of Thanksgiving parties in the ex-pat circles. I hear how the international school does a huge Thanksgiving luncheon. So does the YMCA. I hear from a friend’s friend that they had talked to someone (Japanese) in the Costco bakery (who used to live in Salmon, Idaho!) and speaks great English. This person tells them that the weekend before Thanksgiving would be the last of the pies. It never occurs to me that there would be no pie. That is all Emi really wants.

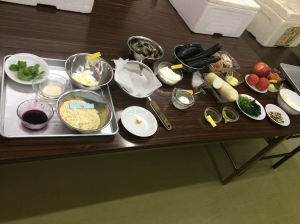

Through texting it becomes obvious that I need to do two luncheons. So on Wednesday the cooking school friends will come and then on Thursday Emi-san and her friend, Kaori-san, will come. At the time, it didn’t feel like that big of a deal. I talk to my mom about the menu. She is good at reining me in. Keep it simple. Remember to save your potato water for the gravy. As I envision the day, I realize I need serving bowls for the guests of honor-fresh cranberry sauce, gravy and mashed potatoes. Emi’s favorite is stuffing, but we had had an in-depth discussion about the heartache of making family favorites in a foreign country. With no oven, roasted turkey and stuffing is not on the menu. This will be a stovetop Thanksgiving-with chicken.

There would be no pumpkin pie. It had been “discontinued”.

“Do they know this Thursday is Thanksgiving in America?!” I screech. Immediately apologizing to the wide-eyed bakery person half my size. Get a grip girl I tell myself. It’s just pie. Kind of.

The night before the luncheon I can barely sleep. So many things I think will work but really haven’t tried. My stovetop is complicated. Only two pots work on the back burner, and those pots don’t work on the two front burners. I have a medium and small skillet. Luckily, they all are non-stick. Food needs to be served hot to be delicious. How will I reheat the chicken? The microwave doesn’t work that great. I want it to be like a real Thanksgiving.

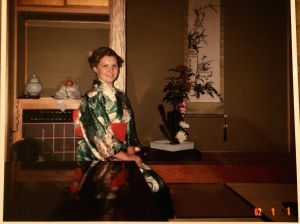

The table alone will seem exotic to my friends. I have a tablecloth, salt and pepper, relish tray, a dish of butter. Single dinner plates from Idaho, flatware, napkins, these are all things my friends only encounter at restaurants. Lulu has come early and she sets the table while I juggle the food on the stove. Brent Jensen’s “The Sound of a Dry Martini” plays in the background, just like it would on Bruins Circle.

My friend, Amy, had sold me fresh potatoes from the YMCA farm. I remember to save the water when I drain them; a good thing too because the gravy needed it. As I mash the spuds, their color seems so strange to me. A creamy yellow, not the fluffy white of a Russet. I was raised in Bingham County, Idaho. We grow the best potatoes in the world. The russet has flavorful skin, white flesh that cooks to a light fluffiness, and flavor that accentuates the meal. The spuds I was mashing smelled good, but absorbed the butter and milk like a sponge. I could feel their weight on my masher. Not the lightness of a russet. My mind thinks about my mom and grandma. They taught me how to cook and I am so glad. Today is taking a lot of thinking/cooking on my feet. It feels like I am improvising everything.

As I talk to myself, I hear my mom or grandma’s input. Gratefulness washes over me. I come from a line of women who take great pride in being able to cook a delicious meal. It is how we show love. I was taught the details matter. The more you think of the details the deeper the expression of love. Providing hospitality is very important work. It begins with a clean, inviting home, and ends with a delicious meal served in a beautiful way. I did not say fancy. In my family our work, homemaking, has never been dismissed as easy or meaningless. Quite the opposite, it is because of what we provide that the ones we love can learn, work, live well.

Ping Pong-its Japanese for ding-dong.

On the monitor two excited lovely Japanese ladies stand waiting to be let in. I hit the key button and they disappear. Here they come! I have slippers waiting for my guests, as all good Japanese hosts do. I have lit my Scentsy apple pie candle. The apple pie I will be serving came from the bakery down the street, but the candle helps give the apartment the smell of Thanksgiving.

Ping pong.

I wish I could give our greeting justice on paper. Tomoko-san is a very expressive Japanese woman. The minute she walks in she is squealing and saying in rapid Japanese that it smells wonderful, different, thank you, thank you for having her and that she is starving. Behind her is Rie-san. She is more reserved, and walks in with an arm full of presents-flowers, a vase, and recipe help. I introduce Lulu, who happens to be Chinese. Their reaction to Lulu is like everyone else’s. “You look Japanese!” Lulu bows and nods, as they try not to speak Japanese to her. We are speaking broken English/Japanese, all at once to each other. With each detail noticed, Tomoko squeals and speaks Japanese, then apologizes and broken English ensues.

Luckily I had found some perfectly suited serving dishes. As the girls chat, I dish up the spuds and gravy, put the poultry on a platter, grab the sweet potatoes, and the cranberries. Everyone sits down. They hold their hands up palm to palm, bow and say “Itedakimasu” which means “we are about to eat a feast”. It is said before any meal.

“Wait” I say “since this is an Idaho Thanksgiving, I am going to say grace. My family prays before we eat, so lets join hands.” They look at each other. Arms encircle the holiday table. Then I say aloud and slowly, “Thank you for this beautiful meal, my new friends, and all who can not join us. (My voice cracks as I think of my family back home.) Amen”.

“Amen” they all say.

Everyone is looking at me. They don’t know what to do. Japanese meals are dished in the kitchen and placed at the table each dish in its own vessel. So I hand the meat platter to Tomoko-san and tell her to take some and pass to the left. Rie-san takes it, places some meat on her plate and gingerly hands it to Lulu. Awkwardness is evidence of its newness. I show them how to make a little well in their mashed potatoes for the gravy. “Oishisoooo! (It looks so delicious!) Tomoko exclaims each time I hand her a dish. I notice that they very purposefully put their food on their plate, just like we do at cooking class. Rie-san delicately places it in the center of her plate, like an artist adding paint. As I am looking at her plate, I notice she has no gravy. “You don’t have any gravy!” I exclaim. As she gingerly reaches through the table, another culture teaching opportunity presents itself. “When we want something, we say, ‘please pass the gravy’”. Tomoko tries, “Pureesu pasu za gurabi sausu”. They call it gravy sauce. More squeals and exclamation of joy as each person asks to have something passed. Who thought eating could be so exciting.

It won’t be the only time we practice words and sounds. We look at each other as they make the sound attending to where our tongues are to make the sound. We work on the difference between the word ‘alive’ and ‘arrive’. Tomoko looks at me, shrugs and says, “they sound the same to me”. These exchanges always end in laughter; the women’s cultural veil of properness dropping, and then they let it all hang out. It’s at these times that it doesn’t matter our language, our age, our standing. We friends talk frankly about their lives and ask frank questions. It is a safe place.

Ping pong.

It is Chikako-san. She is due any day with her first baby, but she isn’t going to miss Idaho Thanksgiving. We eagerly, noisily greet her as she waddles in. I quickly make her a plate as they find her a spot. To my horror, it is now that I realize that the microwave has made the sweet potatoes inedible. Lulu is introduced. Again she hears how she looks Japanese. Then Chikako-san does an amazing thing. She looks at Lulu and says in English, “You are very beautiful. You have beautiful skin.” When I met Chikako-san she barely spoke two words. She did not make eye contact. Today she is not shy. It is Lulu’s turn to blush. The others agree and tell her she is beautiful. How welcoming they made her feel. I notice throughout the meal, Rie-san would ask Lulu about China or her family. Lulu explains that she met her husband at the University of Idaho, where my sons go to school. Chikako-san follows suit and asks Lulu if she has been anywhere other than Idaho and Hiroshima. “Europe and…

Instantly the Japanese begin shrieking! “Eeeeehhhhheeee!” “Honto niiiiii!” These high pitched female Japanese vocalizations are unique to their gender. This reserved gender is allowed to loudly express their surprise, or amazement in high-pitched utterances. And boy did they in my apartment. I started laughing and then we all were laughing. This uninhibited display of emotion is evidence that Lulu and I are in the inner circle of Japanese friendship. At this moment I am acutely aware that I am experiencing authentic friendship.

Suddenly there is rapid Japanese talking. Tomoko, Rie, and Chikako are speaking to each other very directly. It sounds so different than English. It’s soft and fast. I can barely make out any words. Then they are finished. It turns out that the three of them had run into each other at a store and found out that they had all been invited here. When I had texted, I had invited each one in basic English. So there at the table the girls made a group chat through Line (this is a new communication app in Japan that everyone uses because it is free). Tomoko uses a photo of my taco soup as the icon. When I get invited it say Hart. I ask, “What is hart?” Tomoko looks confused. She points to her heart. Oh! We are the HEART group. Our phones start beeping and buzzing with invitations. Rie-san is helping Lulu figure out the app. Community building.

“I love these!” Tomoko is holding up a black olive. She tells me they are much better than the ones she has had in the past. I show her how when I was a kid would eat them of my fingers. The black (kuroi) olive fits nicely on her Japanese finger. Being that I bought the olives at Costco, I had a to buy eight cans. I now know what my omiyagi-souvenir gift-will be. They also love the pickles and green olives. Tomoko ended up eating two plates of food. “I do not want to stop eating!” Another beep.

It’s Tomoko-san’s phone. Time to go. She looks at me with her sparkling dark eyes. “Time go so fast here.” Rie-san is catching a ride with Tomoko-san. Chikako-san is obviously uncomfortable. The luncheon is over. I get out the red olive cans. More squealing. Chikako-san regains her composure and speaks English. “Ahribbisu”. One last practice of the tricky sounds of l, r, and v. Traditional Japanese behavior kicks in with deep bowing gratitude, while speaking “thank-you” and “domo arigatou gozaimasu”. Then we look at each other, and fall into hugs, departing American style.

My apartment is immediately quiet. Lulu gets busy washing the mountain of dishes in the sink. I put the leftovers away. I think about how in my family the women back home would go for a walk and the men would clean up. My Idaho family is sleeping right now. With kitchen back in order, we walk to the train station reflecting on the day’s events. Lulu gushes. She lives in the small town, Saijo that the Micron fab resides. It is a forty-minute train ride from Hiroshima. At the gate Lulu gives me a big hug. Her beautiful, shining, brown eyes thank me for the day. I walk home thankful for friends, family and food

These are the dreaded path entrances.

These are the dreaded path entrances.

These are the gates.

These are the gates.

One day we biked on Etajima-Cycle Island

One day we biked on Etajima-Cycle Island